British test pilots from BAE Systems have lifted the lid on how they push the Eurofighter Typhoon combat jet to the edge of its limits as part of an ‘ultimate test drive’ before delivering the aircraft to customers including the Royal Air Force.

The jet’s power, speed and agility are all brought to the fore as test pilots, based at Warton, Lancashire, take the controls of each Typhoon for the first time – as soon as they roll out from the factory floor to the runway.

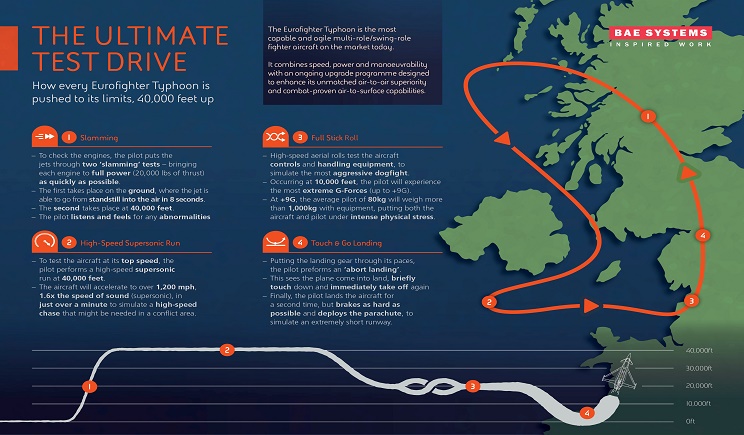

Known as Production Flight Acceptance Testing (PFAT), each Typhoon aircraft is pushed to its limits for up to 60 minutes, flying out from Warton over the Irish Sea at heights of up to 40,000 feet, reaching more than 1.6 times the speed of sound and handling at the most extreme G-forces.

What’s involved in each flight of Production Flight Acceptance Testing (PFAT)?:

Stage One - Slamming

To check the engines, the pilot puts the jets through two ‘slamming’ tests – bringing each engine to full power (20,000 lbs of thrust) as quickly as possible.

The first takes place on the ground, where the jet is able to go from standstill into the air in 8 seconds.

The second takes place at 40,000 feet.

The pilot listens and feels for any abnormalities that might indicate a problem.

Stage Two - High-Speed Supersonic Run

To test the aircraft at its top speed, the pilot performs a high-speed supersonic run at 40,000 feet.

The aircraft will accelerate to over 1,200 mph, 1.6x the speed of sound (supersonic), in just over a minute to simulate a high-speed chase that might be needed in a conflict area.

Stage Three - Full Stick Roll

High-speed aerial rolls test the aircraft controls and handling equipment, to simulate the most aggressive dogfight.

Occurring at 10,000 feet, the pilot will experience the most extreme G-Forces (up to +9G).

At +9G, the average pilot of 80kg will weigh more than 1,000kg with equipment, putting both the aircraft and pilot under intense physical stress.

Stage Four - Touch & Go Landing

Putting the landing gear through its paces, the pilot performs an ‘abort landing’.

This sees the plane come into land, briefly touch down and immediately take off again

Finally, the pilot lands the aircraft for a second time, but brakes as hard as possible and deploys the parachute, to simulate an extremely short runway.

The tests are designed to ensure the aircraft is the perfect product for the customer in terms of safety and performance.

Nat Makepeace, Typhoon Test Pilot for BAE Systems, said:

“The testing is all part of ensuring the performance of the engine is guaranteed. It is extreme flying but in a sense this is the whole point of a PFAT. We are giving the aircraft a thorough workout through all of its capabilities — at high speed and low speed and we slam the engines in a way that would not happen in normal flight.

“After making a rapid climb to 40,000ft I slow right down to a point where we can barely fly and then slam the engines into full throttle.

“This is one of the most critical test points because at 40,000ft you’d typically be flying at 0.9 Mach, but we are back at 0.5 Mach — that’s only 150 knots, which is not much more than landing speed. At this height the air is only a 10th of the density compared to ground level. Even in full reheat the aircraft struggles to stay level. You are moving in a very challenging way. We’re flying as slow as we can and then we slam the engines.”

Even before the pilot leaves the ground they take the nose wheel steering out to make sure the flight control system is working correctly before pulling straight into a steep reheat climb.

Nat continues:

“We have to check the maximum and minimum G, that’s usually around +9g and -3g, at high supersonic flight to give the flight controls a full workout. That is phenomenal performance. You are basically going to the limits that the aircraft was designed for. You are doing things with the aircraft that would never normally be done by the aircrew, except perhaps in real combat situations.

“At 25,000ft I shut the engines off one at a time. It is the only time in normal service it occurs. We shut it off for a minute and then relight it again. Then you drop down to about 10,000ft and fly upside down for 30 seconds. Even a display pilot doesn’t normally do it for that long. Then I drop to 2,000ft and slam the engines again. This is one of the most dangerous phases because if anything was to go wrong you don’t have a lot of time to react.

“Even the first landing is extreme. I deploy the parachute and stamp on the brakes, which heats the brakes and tests the anti-lock system. Everything is beyond what you would do on a normal flight, but within cleared envelope of the aircraft.

“A PFAT is a high workload flight and it’s demanding for a pilot. It is the ultimate test drive. There’s constant noise and vibration and all the time you’re making notes, recording times, and moving on from test point to test point. It’s a discipline and one that’s carried out by every partner nation. There are more than 100 test points but you can split it into two parts: the aeromechanical, like the engines and controls, and then the systems and avionics.

“Testing the airframe and engines takes you to the limits of the aircraft’s design. We are testing to ensure the aircraft is safe. In essence, what we are trying to do is say the aircraft is built perfectly. PFAT is the pilot’s quality control stamp in what is otherwise an extremely complex engineering process. It is the aircrew saying the aircraft is ready to hand over to the customer.”